The Grime Guardian: Building Stateful Multi-camera applications with Groundlight

Groundlight has a Problem

Here at the Groundlight office we have a bit of a problem - sometimes we leave dirty dishes in the office sink. They pile up, and as the pile grows it becomes more and more tempting to simply add to the pile instead of cleaning it up. It was clear that the Groundlight office needed a “grime guardian” to save us from our messy selves. One day, I realized that this was the perfect problem to solve using Groundlight’s computer vision SDK. I could focus on developing the complex embedded application logic while Groundlight handled the computer vision. My design provided me with an opportunity to test out a handful of interesting design patterns, including deployment on a Raspberry Pi, multi-camera and multi-detector usage, a microservice-like architecture achieved via multithreading, and complex state handling.

The Groundlight office sink, where dishes accumulate faster than git commits.

Overview of the Application - The Grime Guardian

The application I developed, the Grime Guardian, is designed to make it fun for the Groundlight team to clean up dishes that have been abandoned in the sink (source code). Using two cameras, the application monitors the state of the office sink and the overall kitchen scene. If it recognizes that dirty dishes were left in the sink for over a minute, it posts a funny yet inspiring message and photo to a Discord server that alerts the Groundlight team and encourages someone to help. Then, while the dishes remain unattended it surveys the kitchen until it sees someone. Once someone comes to help, it posts a message and photo, celebrating them as a hero, giving everyone in the Discord server a chance to recognize them. While this is cheesy, it has made it a bit more fun for us to do the dishes!

The Grime Guardian alerting the Groundlight Team through Discord

Architecture of a Sophisticated Groundlight Application

The Grime Guardian demonstrates how to build an advanced Groundlight application in a handful of ways:

- Raspberry Pi Deployment - The Grime Guardian leverages our custom Raspberry Pi Image, which makes it easy to deploy Groundlight applications on Raspberry Pi.

- Multiple Cameras - The Grime Guardian actively uses more than one camera to solve a problem (it has one camera pointed at the sink and one pointed at the general kitchen scene).

- Multiple Detectors - The Grime Guardian combines multiple Groundlight detectors to solve a problem.

- Microservice-like architecture via Multithreading - The Grime Guardian’s architecture is broken down into a handful of microservice-like processes - each running in a different thread on the same machine. This improves the app’s robustness and allows for more flexibility and scalability.

- Complex State - As described in the previous section, the state of the world this app is tracking is somewhat complex. In addition to knowing the state of the sink and kitchen, the app tracks how recently the state was updated and how recently it has sent a notification to the Groundlight team.

- Discord Bot Integration/Notifications - The Grime Guardian uses the Discord Bot API to send notifications to a Discord server. Discord can be an extremely powerful and flexible tool for building applications (e.g. Midjourney).

- Robustness - In practice, the Grime Guardian has been extremely robust, with only one or two incorrect (false positive) notifications over many weeks of deployment and hundreds of thousands of Groundlight queries.

Microservice-like Architecture

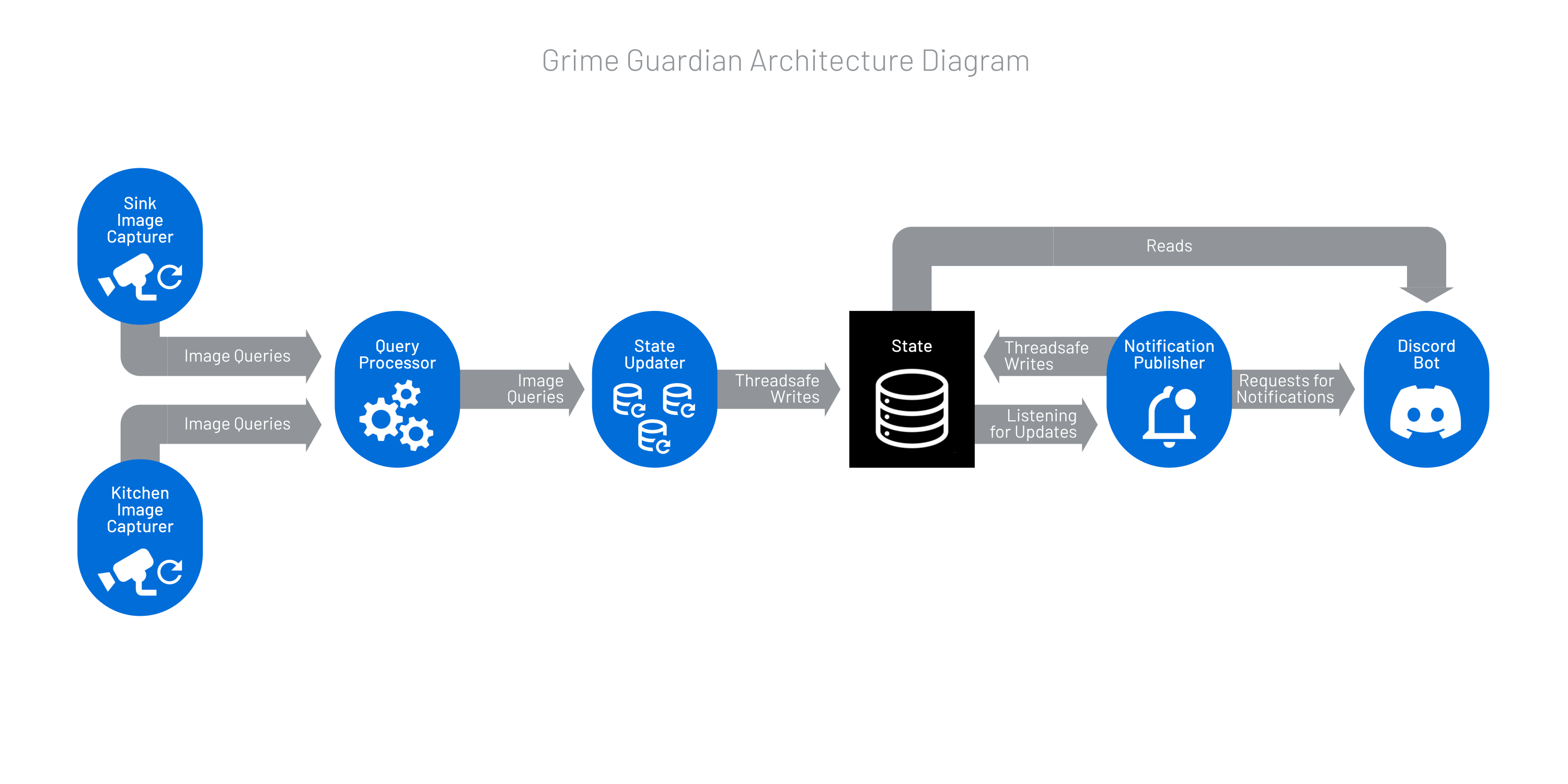

The Grime Guardian leverages a microservice-like architecture via multithreading to enhance its performance and robustness. Each microservice within the application runs in its own thread on a single Raspberry Pi, allowing for simultaneous execution of tasks. This architecture is particularly beneficial in this context as it allows the application to monitor the sink and the kitchen scene concurrently using two cameras, and to process the data from these cameras independently. Furthermore, it enables the application to manage complex state tracking and Discord notifications without blocking or slowing down the image processing tasks.

The application is broken into six microservices:

- Sink Image Capturer: This microservice captures images from a camera pointed at the sink and submits them as queries to a Groundlight detector via the

ask_asyncSDK method (this method is useful for times in which the thread submitting image queries is not the same thread that will be retrieving and using the results). I set the detector's query to "Is there at least one dish in the sink? Cleaning supplies like a sponge, brush, soap, etc. are not considered dishes. If you cannot see into the sink, consider it empty and answer NO" and set the confidence threshold to 75%. After Groundlight replies with a query ID, the service passes the query ID to the Query Processor service. - Kitchen Image Capturer: This microservice is identical to the Sink Image Capturer except it uses the camera that can view the whole kitchen and submits images to a detector with the query "Is there at least one person in this image?" and set the confidence threshold to 75% as well.

- Query Processor: This microservice processes the queries passed to it by the two Capturer services, waiting for confident answers from Groundlight and filtering out queries that do not become confident within a reasonable time (I chose a 10 second timeout as that was how frequently each Capturer service submitted a query to Groundlight). Queries that become confident are passed to the State Updater service.

- State Updater: This microservice updates a complex model of the application's state based on Groundlight's responses. It tracks the status and last update time of the sink and kitchen, the image query IDs that led to the current state, and the timestamps of the last clean sink and notifications sent.

- Notification Publisher: This microservice listens for updates to the state of the application (written by the State Updater) and decides whether it is appropriate to send one of two possible notifications. If a notification is needed, it adds it to a queue of notifications to be processed by the Discord Bot. Importantly, the Notification Publisher only determines if a notification should be sent. It does not handle the mechanics of what data to send or how and where to send it.

- Discord Bot: This microservice runs a Discord bot, which listens for requests from the Notification Publisher. When a request arrives, the bot collects the relevant data and sends notifications to a Discord server.

Diagram created by Jared Randall

Architecture diagram for the application

State Management and Notification Logic

The Grime Guardian's ability to track and manage a complex state is a cornerstone of its functionality. The application not only needs to know the current state of the sink and kitchen but also when these states were last updated and when the last notifications were sent. In total, the application needs nine separate variables to function properly (a combination of binary-encoded state fields, timestamps, and image query IDs). This level of detail is crucial for avoiding redundant alerts and ensuring timely and accurate updates.

As seen in the architecture diagram in the previous section, multiple services read and write to the state simultaneously. To handle this complexity, I implemented a wrapper around the state to handle reads and writes in a thread safe manner. This wrapper ensures the state can be accessed and modified safely across many services. It uses a lock to prevent race conditions, ensuring that only one thread can modify the state at a time.

import threading

import copy

# simplified version of how the Grime Guardian manages state safely

class SimpleThreadSafeState:

def __init__(self):

self.state = False

self.lock = threading.Lock()

def update_state(self, new_state: bool):

with self.lock:

self.state = new_state

def get_state(self) -> bool:

with self.lock:

return copy.copy(self.state)

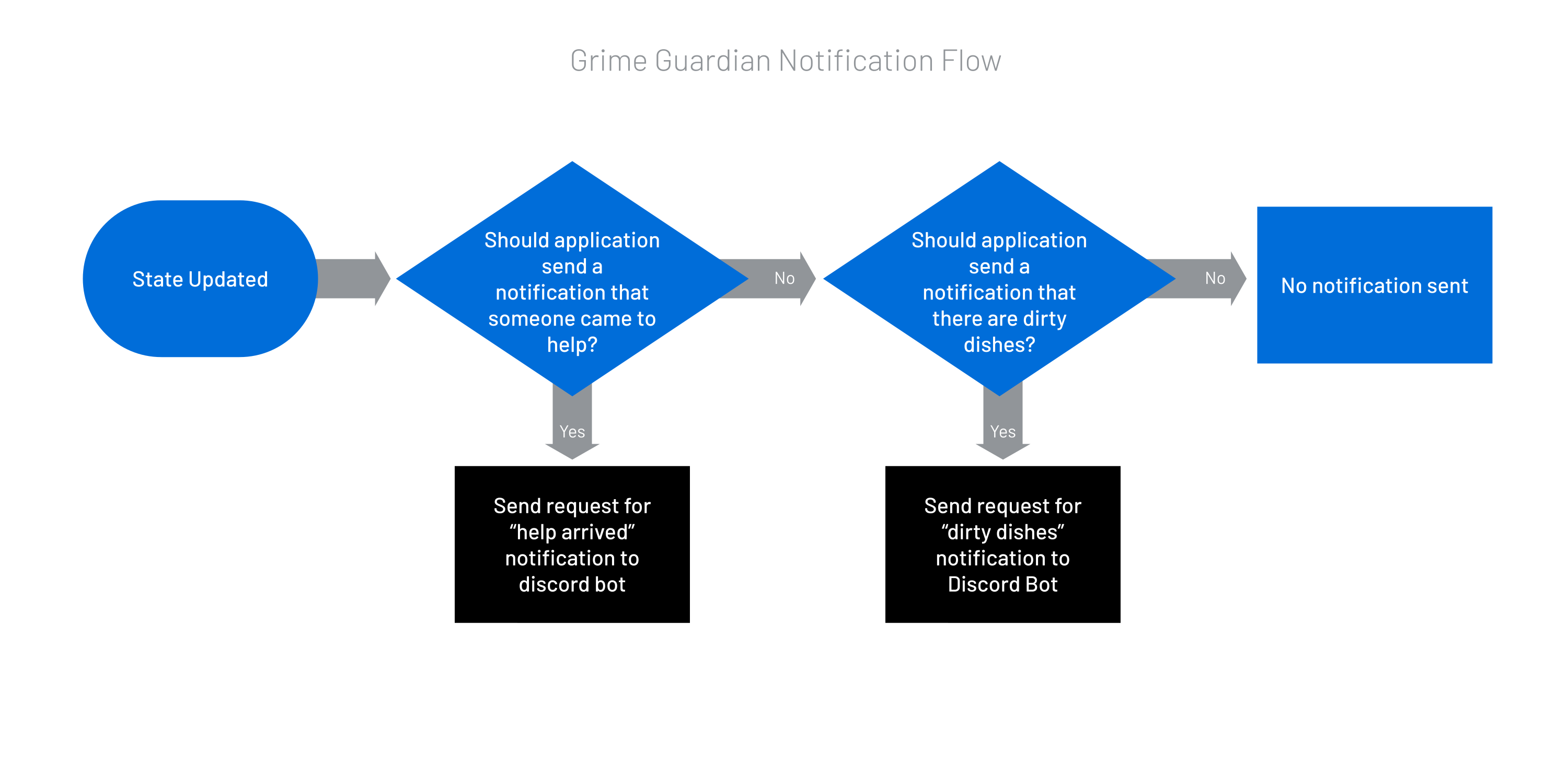

The application uses this state to determine when to send notifications. I've tried to break down this logic into a few of flowcharts. At a high level, the logic is pretty simple. Whenever the the application's state is updated, the application performs a check to determine if the new state justifies sending each type of notification.

Diagram created by Jared Randall

High level flow for determining if a notification should be sent

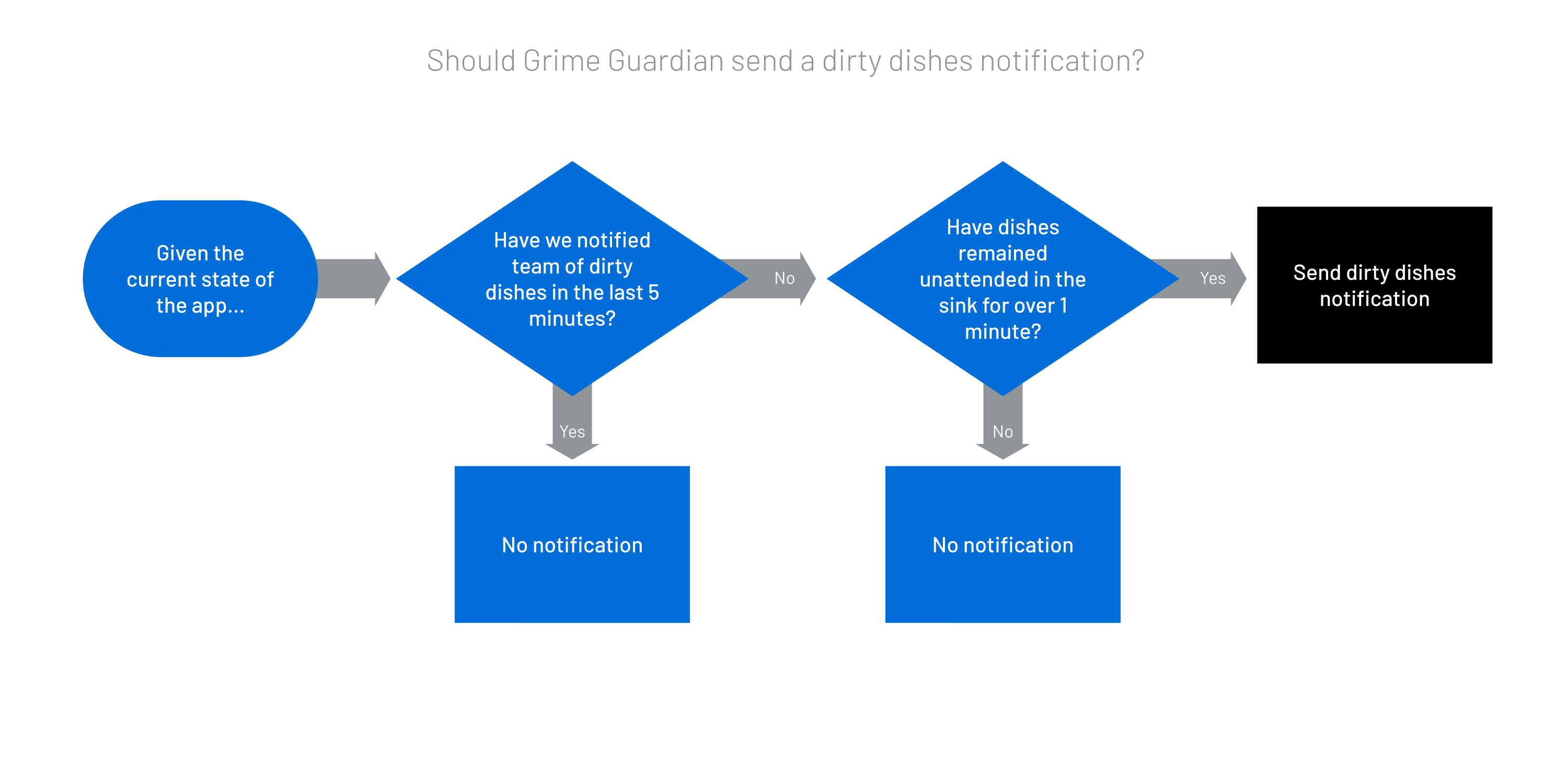

The logic for determining if each notification should be sent is a bit more complex. It first checks for the last time a notification was sent. If the last notification was sent in the last 5 minutes, no notification is sent. This is important as it prevents the application from spamming the Discord server with notifications. Next, the application checks if the sink currently has dirty dishes in it, and how long it has been since the sink was empty. We only send the notification if dirty dishes have been present for more than a minute. This approach ensures that the Grime Guardian does not send a notification every time someone puts a dirty dish in the sink, but only when dishes have been abandoned for a while. This ensures that the app only notifies the team when it is actually needed.

Diagram created by Jared Randall

Flow for determining if the dirty dishes notification should be sent

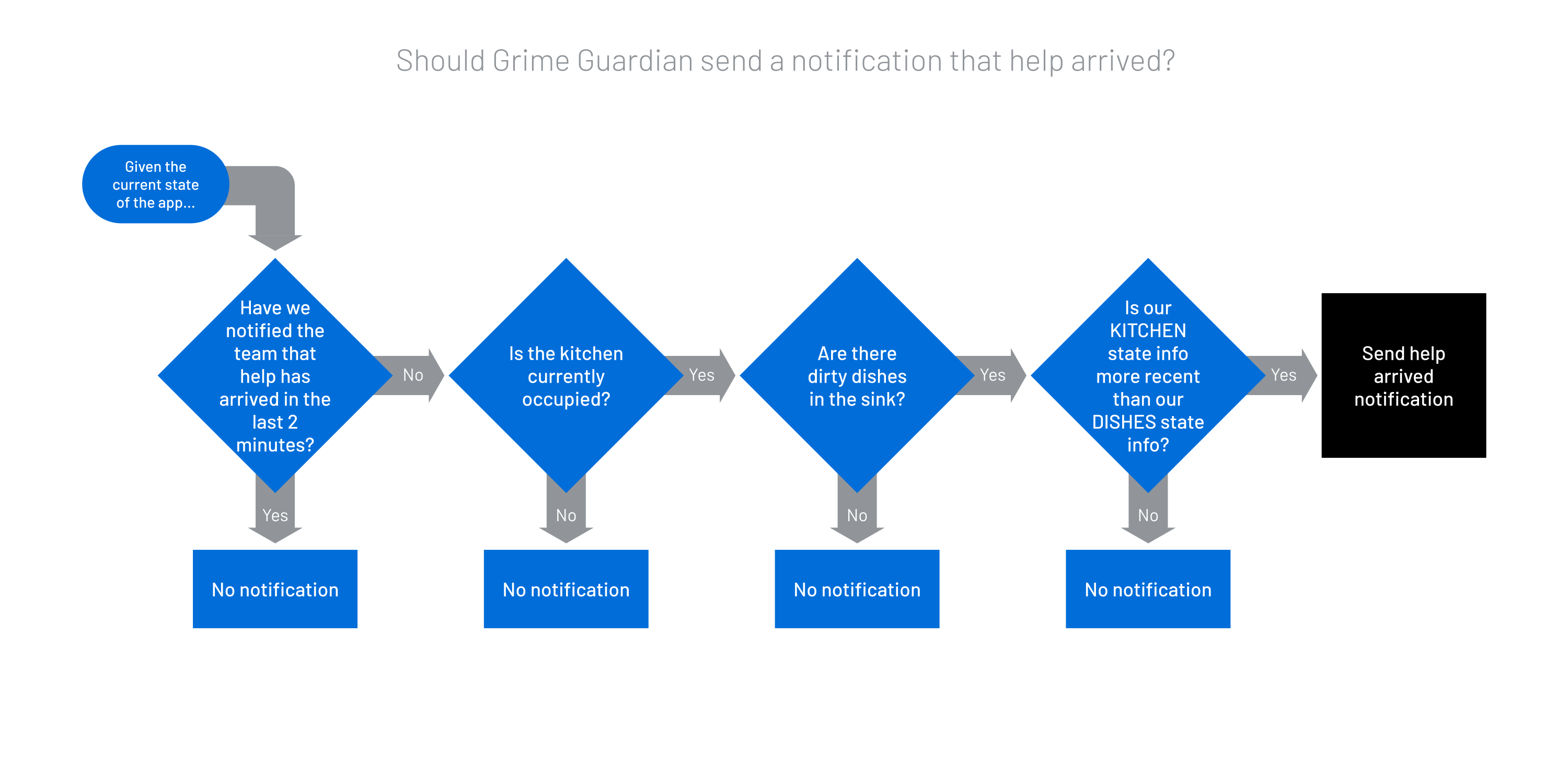

The logic for determining if someone has arrived to help is similar. We have a check that ensures we do not spam the Discord server. Then, we only send a notification if there are currently dishes in the sink and someone is present in the kitchen. This ensures that the Grime Guardian does not send a notification every time someone walks into the kitchen, but only when dishes are in the sink.

Diagram created by Jared Randall

Flow for determining if the help arrived notification should be sent

In retrospect, getting the notification logic to work properly was one of the more challenging parts of this project. The version I presented here is the result of many iterations and tweaks based on real world usage and results. I think this is because this logic is an expression of the application's core value proposition. If this "business logic" is not correct, the application will not be fun or useful. Fortunately, Groundlight enabled me to focus on this logic and not worry about the computer vision.

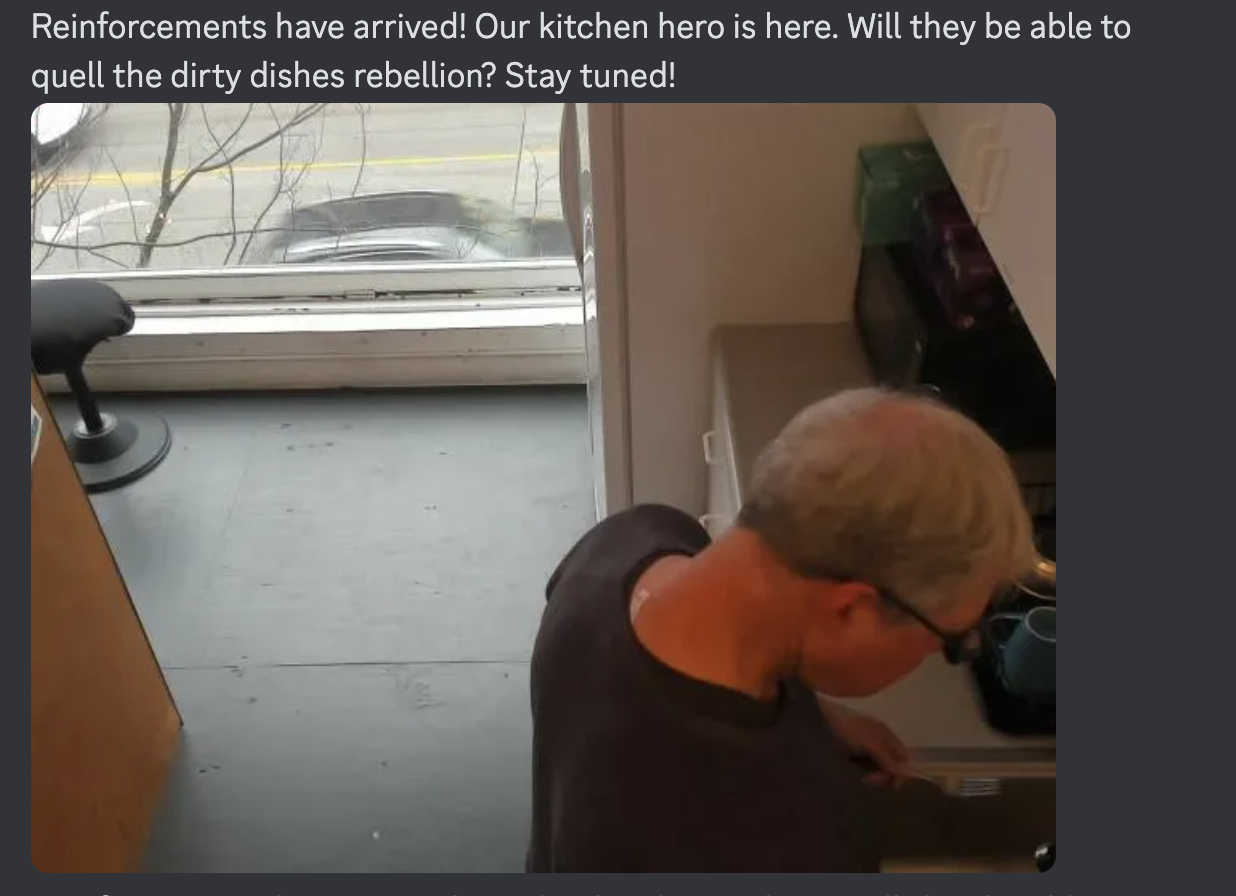

Discord Bot Notifications

The Grime Guardian uses the Discord Bot API to send notifications to a Discord server I set up. At startup, Discord requires some boilerplate to handle authentication. After this is done, the bot listens for new notification requests from the Notification Publisher. Based on the type of request, the bot collects the relevant information (e.g. the image of the dirty sink, or the person doing the dishes) and sends the message. The Discord Bot API makes this incredibly simple, after handling authentication, a new message and an attached image can be sent in a single line.

await channel.send("message", file=discord.File(fpath))

While I did not have time to add more complexity to the bot, Discord’s strong documentation gives me confidence it would not be that hard to add more features. For example, it would have been nice if the bot could listen for replies or emote reactions to its notifications - if the bot reported that the sink was full of dishes when really it was not, I could react to the notification with an emote that indicates the correct label for the image, and then the bot could automatically send this information to Groundlight, improving ML performance.

Future Improvements and Enhancements

Extending the functionality of the application, I can imagine adding motion detection to limit the frequency of image submissions to Groundlight. Currently, the application sends images to Groundlight at a fixed interval (every 10 seconds), regardless of whether there has been any significant change in the scene. This approach, while simple, could be optimized to become more cost effective. As it is now, it can lead to unnecessary image submissions when the scene is static. By incorporating motion detection, the application could intelligently decide when to send images to Groundlight. Fortunately, some of my excellent colleagues have built framegrab, an open source tool that automatically handles this.

Build Your Own Grime Guardian

Thank you for taking the time to read my post! As I reflect back, I’m very proud of how Groundlight enabled me to very quickly and effortlessly stand up an ML solution to solve a simple office problem in a fun and engaging way! If you are particularly interested or inspired, I encourage you to check out the source code. Feel free to open a GitHub issue with questions or submit a PR with improvements!

The Grime Guardian celebrates Tom, my colleague, for his heroic cleaning effort. The grime is no match for his dish-defeating determination!